It’s unlikely that most of those in the room had ever experienced what they were about to go through. The room is Mission Control for the International Space Station at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. On the last Thursday in July 2021 (a week ago as I write this), after a very tense docking of a big new Russian module, there is suddenly an alarm signaling the station is moving in an unexpected, potentially dangerous way. Those in the room are about to be thrown into a “spacecraft emergency.”

While you may have been working from home that Thursday morning, I was watching the docking of the “Nauka.” It is the Russian Multipurpose Laboratory Module, a big node added to the station giving the Russians much more work area. It also signals the Russians may remain partners at the station longer than many expect.

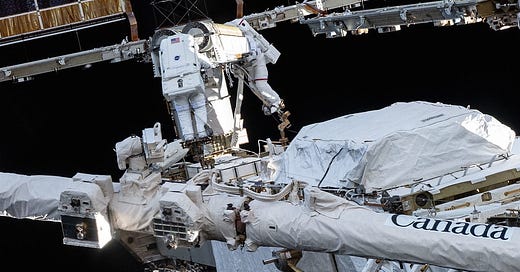

Credit: NASA

NOT A NORMAL DOCKING

That docking was scary. Usually the mating of a vehicle and the station appears quite routine. This one wasn’t. Then, a bit later it got worse. The entire station took a one-and-a-half rotational backflip caused by a malfunction of the new module. The space station, its modules, solar arrays, trusses all flipping in space. The Russian module started all this, on its own, firing its thrusters. You may not have heard about this "emergency." Now, we know it was worse than we thought.

For many, viewing a docking might be like watching paint dry. I enjoy the zero-g dance of two pieces of metal connecting. This docking got my heart racing.

The Russian module is fully autonomous. It relies on its computers to slowly bring it closer and closer to the station for the docking. But, as it was approaching, the computers and thrusters had trouble keeping the massive piece of space hardware on course. I was getting nervous. I’ve performed plenty of docking simulations. Trust me, those docking sims are tricky to complete smoothly.

There’s a little crosshatch on the station that the module's camera is supposed to lock onto. We’ve seen this with the Dragon capsule, Soyuz, and other vehicles arriving at the station. But Nauka, 43 feet long and a mass of 2 ½ tons of steel and equipment, can’t stay on the target.

The cosmonauts call out that it’s “off a square” on the grid they are looking at. Finally, just under nine meters to docking, Moscow orders one of the cosmonauts to take manual control. He does a great job and keeps the target centered all the way to docking. Phew!

ALARMS!

The trouble, however, is far from over. Just 3 hours after docking alarms start sounding. Controllers in Houston and the 7 astronauts/cosmonauts on the space station would have heard the alarm at the same time. The station was moving. And no one told it to move.

The just-docked module was firing its thrusters. With the Russian module now bolted onto the station, all those thrusts start pitching “up” the station (pitching up-think of a jetliner when the pilot pulls the nose up). The massive complex is rotating. It's a one and-a-half backflip. The danger is that all that torque from the thrusters could stress the docking joints potentially ripping apart the connection.

(Credit: Scott Manley @DJSnM)

This wasn’t a quick spin. The entire event was less than one hour. The astronauts, according to NASA, didn’t notice that the thrusters were firing (but they had heard the alarm about the station changing its attitude). Youtuber Scott Manley put together an animation that gives us all an idea of how it may have looked.

THE CONTROLLER

In Mission Control, Flight Controller Zebulon Scoville first thought the alarm might be false. When he realized the readings were real he thought to himself, “’Oh, geez, what now?’ and then you kind of push that down and just work the problem,” he told the New York Times. He declared, for the first time in his career, a spacecraft emergency. Such declarations have happened before, but they are rare.

Zebulon Scoville Credit: Twiiter

The problem in this emergency is that the thrusters, controlled by software on the module, can only be overridden from the ground. The space station was not over Russia and its ground stations, so Moscow was unable to get a message to the module to stop firing its thrusters.

Contingency plans call for NASA to give control of the station to the Russians when there is an unexpected movement like this. They did. And about 45 minutes later Roscosmos , the Russian Space Agency, was able to stop the backflip and rotate the station back into the correct orientation.

WHAT HAPPENED?

The Russians are in charge of the investigation and say this was a software problem. Sounds reminiscent of Boeing’s trouble with its software on its first Starliner test flight. The autonomous capsule thought it was at a different point in its flight and started firing thrusters. Did Nakua think it was in free flight and start firing its thrusters while it was actually docked?

Roscosmos will need to provide some answers about this “spacecraft emergency.” What was it like in “that” room the last Friday in July? Just look at Scoville's tweet after declaring his first spacecraft emergency!

Join the conversation over at my Bulletin page.